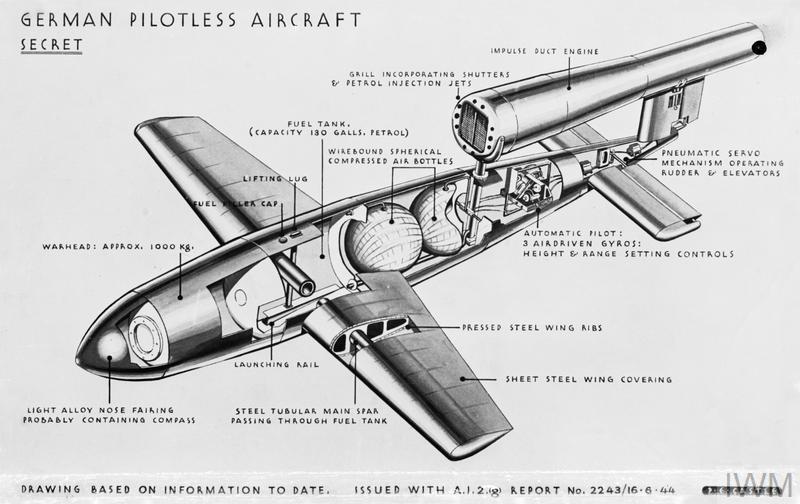

In June 1944 the first German V1 rockets – also known as doodlebugs or buzz-bombs – began to fall on London. Donald MacKay recalls volunteering to help clear the damage caused by the rockets, which struck 80 years ago this month.

“By the summer of 1944 many of those trapped in Manchester’s Heaton Park holding pen (for potential pilots and navigators) were beginning to wonder if they’d ever get to the sharp edge of the war. Little did they know the real war was just a train journey away.

“Soon after D-Day most of us were sent home on leave that began the day after the first salvo of V1s struck London on the night of 15-16 June.

“The morning newspapers only mentioned an air raid on London – a terse paragraph with no details. The Home Office was making sure no news reports would spread ‘alarm and despondency’.

“The cadets who travelled south that morning were in for a shock. I learned from my mother in Tunbridge Wells that pilotless rocket bombs had roared over our house during the night in groups of four. During the next two weeks all of us who lived in Southern England had what we thought was enough of ‘buzz-bombs’. Each ‘southerner’ returned to Heaton Park with his own personal flying bomb tall tale for those uninitiated Scousers, Geordies and Scots who had gone on leave in the other direction.

“Early next morning we were called on parade. Our corporals were clueless; they had no orders to give us and told us just to ‘stand easy’ and wait. Our group of five huts housed about 200 airmen – 200 bods all wondering when we’d get breakfast.

“Eventually a flight lieutenant and flight sergeant arrived. We came to attention. Standing on a box supplied by the NCO, the officer explained that the damage was so great in London from two weeks of V1 attacks that Air Ministry had promised the Home Office a large number of volunteers to repair civilian homes. ‘You will work under works-andbricks NCOs from the Air Ministry Works Department, who are even now being recalled from France and overseas’, he said. ‘Volunteers will take two steps forward. March!’ yelled the Chiefy. Every man stepped forward.

“There was no breakfast. We were soon shuttled, with full kit, to a station nearby where an empty train waited with steam up. We filled it, at least a thousand of us.

“The train, a special, left before noon. We raced along some sections of track, we stood waiting on others. At one station stop, ladies were ready with tea and sandwiches – our lunch. Everything was so organised.

A cutaway and annotated drawing of the V1. ©IWM

“We reached the outskirts of London late in the afternoon. There was much shunting and rattle-banging over spur lines and through goods yards. Those who recognised landmarks said we were heading towards Dagenham, and that’s where we stopped.

“After lining up on a shabby platform, we marched to waiting lorries, and were ferried to a large open tarmac area beside an imposing cluster of brick buildings inside a park-like compound. The gen was that this had been a psychiatric hospital prewar. We were left standing beside our kit for what seemed like hours. Eventually a strange NCO arrived, “Stand easy. You can smoke if you have them.” Then he left us.

“Again we waited; dusk fell. Some began to chant ‘Why are we waiting?’ No one seemed to care. A chap with a great tenor voice began to sing and others, forming a circle, joined in …. “Roll out the Barrel”. A larger circle formed outside the first. Arms linked, we were all singing, a thousand voices in unison: White Cliffs of Dover; Any time you’re Lambeth way; It’s a long way to……. Darkness came, a whistle blew. Silence. ‘Get fell in!’

“Near midnight station admin staff, assembled that day from across Britain, listed our names and numbers and assigned us to empty rooms, once hospital wards, where we left our kit. Outside again, newly arrived cooks prepared gallons of tea, more sandwiches and wads [RAF slang for buns or cakes]. Making two or more trips to a packed warehouse, each man collected the makings of a cot (head, foot and springs); three horsehair palliasses; two blankets. Each ‘room’ was issued one screwdriver, a pair of pliers, a spanner and enough nuts, bolts and washers to assemble the cots. We literally made our own beds – then passed out in them!

“By 0600 hours we were on parade again for breakfast. Someone had worked all night organising the long disused hospital kitchens and setting up tables in the dining room. Scrambled eggs and bangers, lots of tea and jam.

“After breakfast we were sorted into groups of 10 or 12. It was a kind of self-selection conducted by the works-and-bricks flight sergeants who came onto the parade grounds, approached a couple of airmen and told them to get their mates together to form a work party. Every work party was ‘issued’ with one commissioned officer – an aircrew type either taking a rest from a completed tour or recuperating from wounds.

“Did any of us hold a driving licence in civvy street? ‘If yer did, or if yer can drive a ve-Hicle even wivout a licence, step over ‘ere.’ Those who stepped over were led off to the Dagenham Ford test track where they were put, solo, into a 10-ton garry and turned loose. If they made it round the track without a prang they were given a temporary driver’s licence on the spot, issued with their test drive garry, and told to drive it back to the parade ground. That took some special organising. The work party in the meantime had been assigned its own commandeered civvy bus with a pukka RAF Military Transport driver.

“We climbed aboard the bus, and with the garry following, drove to a railway goods yard where a long goods train stood at a siding. Some wagons were full of new hammers, others had spades or shovels, saws or crowbars; some were stacked full of extension ladders or wheelbarrows; some with coils of rope or kegs of nails. There were vans full of old and new tarpaulins, ‘donated’ by all of Britain’s railways, LMS, LNER, Southern stencilled on them.

“Our ‘flight’ had a list of equipment each work party was supposed to acquire. ‘Forget that,” he said, “We’ll need everything we can scrounge. Load it all in the garry, and quick before they catch us.’ We knew then that we had chosen the right boss.

“Back to base for lunch, then off to our first job. It was in the Lewisham area. On the way we passed a blasted street where Civil Defence [CD] rescue workers were still digging bodies from a number of flattened shops, destroyed early that morning. Our officer talked us through the police barriers which had closed the road to all but essential traffic.

“We were to work on damage that was a week or more old. New bomb sites were the responsibility of the CD professionals. Our task was to make the ground floor of each damaged house habitable for the occupants. We were told to board up the windows and make sure the front and back doors could be closed. The shattered roof was to be covered with the tarpaulins. Any shaky chimneys were to be knocked down. It was a massive, daunting task as each bomb could blow away the roofs from 15 to 20 homes.

“We all had to learn on the job. Many of us had never climbed a ladder or hammered in a nail. We worked every day until it was too dark to see, right through the peak attacks of July and August – watching other bombs arrive and blow up.

“Orders eventually limited the hours of work and imposed strict dress regulations, which got rid of the battered bowlers, tom toppers, boaters – and the ladies’ bonnets the lads had rescued from the rubble.”

The scene at Clapham Junction, London, after one of the first V1 flying bombs fell. ©IWM

Air Mail

This story first appeared in Air Mail magazine in 1995. To receive Air Mail, which is the RAF Association’s quarterly members’ magazine and looks at all aspects of the RAF’s work, now and since it was founded, become a member and opt for Air Mail as part of your membership.